I made the following remarks during a panel discussion on West Virginia education reform at the 2018 Appalachian Justice Symposium at the WVU College of Law:

Modern education reform in West Virginia began with Pauley v. Kelly. Yet this was the sentiment of author of Pauley, Justice Harshbarger, just six years after that decision: “I see no hope for [West Virginia] schools.” I don’t share that sentiment but, of course, I have the benefit of nearly 40 years of hindsight. Justice Harshbarger was focused on the immediate aftermath of the decision which I will cover momentarily. But I think to fully appreciate the significance of Pauley, we need to situate it within the broader national school finance reform movement that began in the late 1960s.

In that first wave of litigation, plaintiffs asserted that school funding disparities were a form of wealth discrimination caused by the overreliance on local property taxes to finance public schools. These first legal challenges were brought in federal courts seeking recognition of a right to education under the U.S. Constitution, a right plaintiffs hoped would necessitate equal funding of schools.

That first wave crashed when the Supreme Court in San Antonio v. Rodriguez held that education was not a fundamental right under the Equal Protection Clause and that neither poor people nor families concentrated in high poverty school districts constituted a suspect classification worthy of heightened judicial scrutiny. Therefore, school funding disparities need only be rationally related to a legitimate state interest. The 5-4 majority deemed local control over schools a vital state interest that was quote “worth some inequality.”

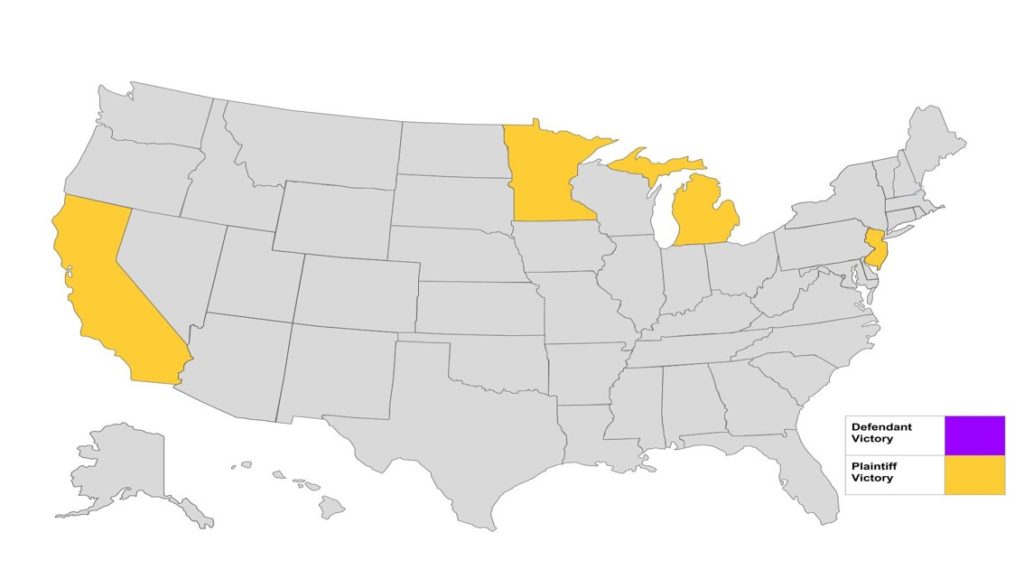

In a footnote in his dissent, Justice Thurgood Marshall suggested that advocates take their legal challenges to state courts instead. Justice Brennan a few years later authored a seminal law review article urging state courts to interpret and give effect to the individual rights guarantees in state constitutions. Well, advocates heeded Justice Marshall’s advice and rode a second wave into state courts; state court judges, in turn, heeded Justice Brennan’s advice and began to independently construe their state constitutional provisions. Pauley was among the first of these second-wave cases.

Now, every state constitution contains an education clause, although the language varies quite a bit. Some clauses simply require a “free” public education; others demand an education that is “general,” “uniform,” “suitable,” “thorough,” or “efficient.” Maryland, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wyoming have the “thorough and efficient” language that is found in the West Virginia constitution.

So, what Pauley did was interpret the thorough and efficient language in the education clause as coextensive with the state equal protection guarantees.

It held that the right to education was fundamental and therefore funding disparities would be subject to heightened judicial scrutiny. Now, if that was all Pauley did, I don’t think there would be much to talk about today. Pauley wasn’t the first state court to hold the right to education fundamental nor would it be the last.

What makes Pauley unique is that it was the first decision in the country to actually define in substantive terms the education clause. It said that a thorough and efficient education develops the minds, bodies, and social morality of children to prepare them for occupations, recreation, and citizenship. But it didn’t stop there.

It went further to articulate eight capacities that a thorough and efficient education should cultivate in children from basics like literacy and math to knowledge necessary to meet the demands of citizenship, even competency in the arts and social ethics.

And there was more, the right to education necessitated good facilities, curriculum, and teachers, accountability mechanisms, and high quality standards. Let me emphasis again that Pauley was the first decision in the nation to go this far in defining comprehensive substantive standards.

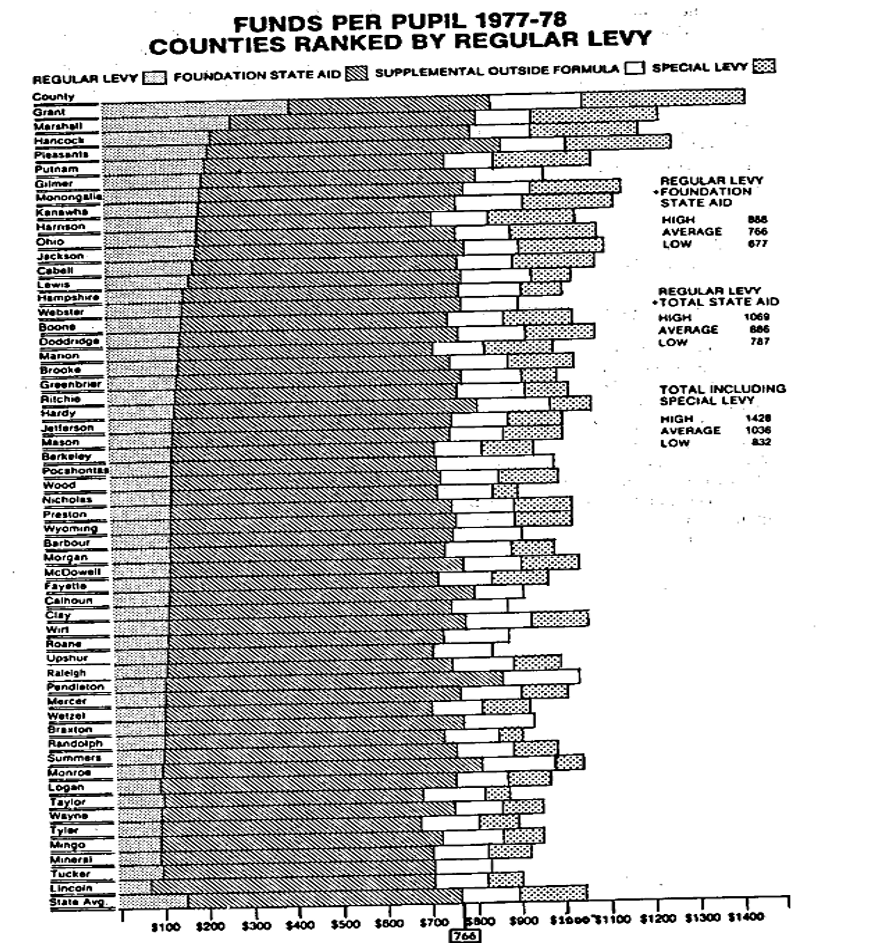

But Pauley was also cutting edge in how it articulated educational equality. This chart in the decision’s appendix shows funding disparities caused in large part by differences in the yield of county taxes through levies and special levies and the failure of state aid to compensate for those differences.

Well, Pauley says the goal is not just to achieve fiscal equalization among the counties, or if you will a horizontal equity. Rather, it is to ensure equality in substantive educational opportunity, a type of vertical equity, where differently situated students have what they need to succeed, “no matter what the expenditure may be.” This was pushing the envelope, ahead of most other state court thinking at the time. So, why was Pauley not a source of great pride for Justice Harshbarger, why was he so disappointed just six years later? Because of what happens on remand.

The trial court over the course of 17 months heard more than 40 days of testimony from more than 30 education experts. At the conclusion of the trial, Judge Arthur Recht issued a 244 page decision describing serious constitutional inadequacies. Judge Recht concluded that the state schools were in quote “outrageous” condition some were actually so bad that they were a serious health hazard, and not a single school in the state met constitutional standard.

There were few in WV that would have disagreed with that conclusion. Yet, the Recht Decision was greeted with stiff resistance from lawmakers because it was perceived to demand too much, too quick.

Judge Recht exhaustively detailed what a thorough and efficient education would entail, down to the appropriate square footage for classrooms and the proper acreage for school facilities. For example, he held that every elementary school student should have at least 100 minutes of art education per week, in an art room of at least 65 square feet, with one-fourth the area of the art room designated for storage.

One estimate for the total cost of implementing the Recht decision was as high as $1.2 billion nearly as much as the state’s entire budget—this, at time when the state was experiencing yet another recession and unemployment was high.

Lawmakers including then-governor Rockefeller were caught off guard by the magnitude of the Recht decision. Rockefeller really set the tone when he went on TV and ridiculed the excesses of the decision, such as heated shower floors and lessons for kayaking. He said he would never raise taxes to implement the decision. Now, Rockefeller later came to regret some of those comments and earnestly supported the Recht decision.

But the die had been cast. Stung by the criticism, Judge Recht issued a supplemental decision just 10 days later denying that he was usurping the legislature or that his decision would cause a massive increase in property taxes. Judge Recht also allowed the state department of education to oversee the development of a master plan to implement the Recht decision. It is somewhat unusual to have the defendant essentially be the court’s special master but Judge Recht might have felt he had no choice given the opposition to his decision.

In any event the state came up with a master plan that detailed higher output standards for educational programming, school facilities, and school finance. Judge Recht approved the master plan, although he rejected the state’s 17 year plan for implementation and said that the plan had to be implemented “at the earliest practicable time.” The WV Supreme Court largely affirmed Judge’s Recht’s decision in Pauley II (styled as Pauley v. Bailey). It then remanded the case to the trial court for further monitoring.

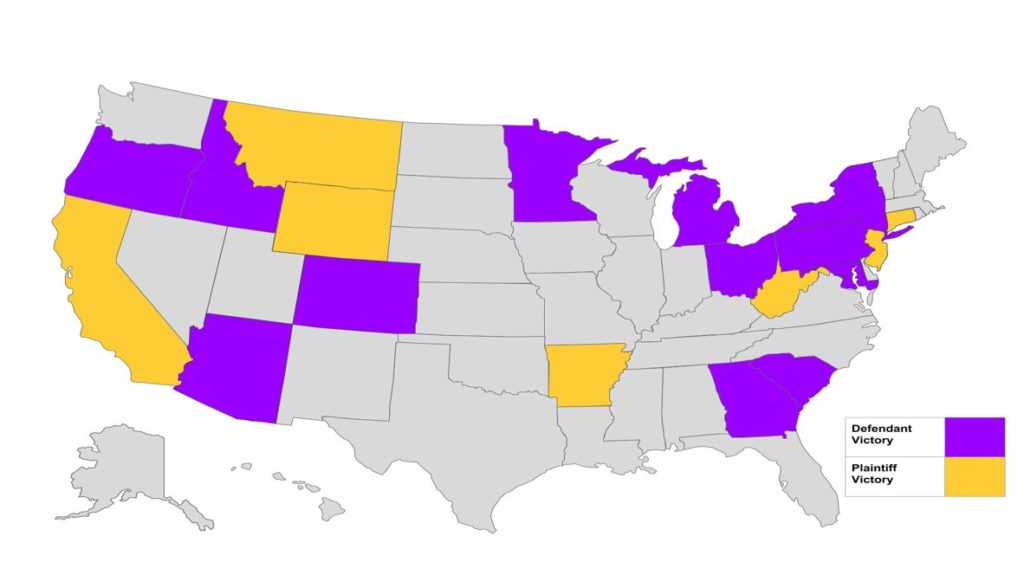

Meanwhile, on the national stage, the third wave of litigation was surging toward educational adequacy with a focus not whether students have the same access to educational resources but whether they have enough funding to meet certain education quality standards.

If that sounds familiar it’s because it is precisely what the Pauley decision did ten years earlier. Yet, it is the Kentucky Supreme Court’s 1989 decision in Rose v. Council for Better Education that is credited with ushering in the third wave of reform litigation and that’s most likely because that decision invalidated the entire Kentucky public education system, not just school financing, but all statutes and regulations relating to education.

Rose has since been adopted or relied on in nearly every other successful state court case for more than two decades nationwide. It is frequently cited for its definition of adequacy and specifically the seven capacities it articulated for all students.

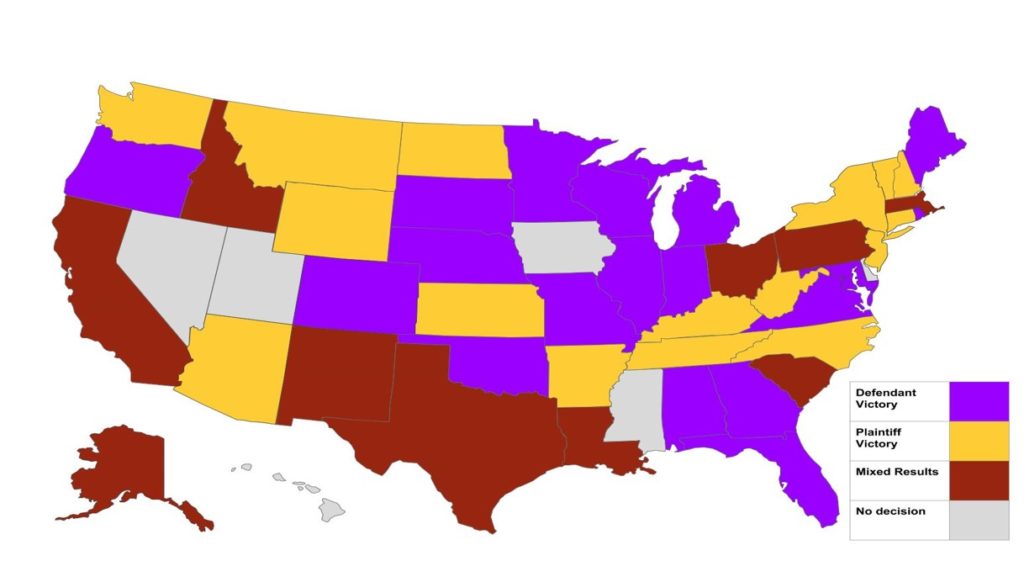

The third wave has enjoyed far greater success than the first and second waves. Plaintiffs prevailed in approximately 75% of adequacy cases from 1989 to 2006. Then, of course, we had the Great Recession and states drastically cut education funding, by more than 20% in some states. That’s when courts began to reject adequacy cases.

Now, some of this can be explained by economic and political realities but I think the predominant reason that courts are starting to retreat from these cases is due to the resistance they are encountering from state legislatures. In some instances, legislatures have outright refused to comply with court orders. One state court took the dramatic step of holding the legislature in contempt for failing to devise a remedial plan.

Now the problem with adequacy in particular is that it demands state action. States have to devise standards, curriculum, and funding and accountability mechanisms to meet the qualitative adequacy thresholds. And in that context courts harbor reservations that they may be intruding on separation of powers by ordering specific remedies or even giving remedial guidance.

It was this tension between courts and lawmakers that stalled progress in WV as well. Governor Arch Moore was adamant that he would decide what’s best for education in WV, not quote “some circuit court judge.” And the legislature took the same attitude, virtually ignoring Pauley I and II throughout much of the 1980s.

By 1995, in the midst of the third wave, a class of Pauley plaintiffs filed a motion to enforce the master plan which had still not been fully implemented. That case, Tomblin v. West Virginia eventually made it back to Judge Recht, after the legislature had enacted a performance-based accountability system and the parties had negotiated an agreement on most points of the litigation.

Judge Recht vacated a prior judge’s ruling that the school finance system was still unconstitutional, reasoning that the new legislation should be given a chance to succeed. He also agreed with the plaintiffs that the funding formula remained defective but not unconstitutional.

By 2003, Judge Recht terminated the court’s oversight, writing from this point forward quote “decisions regarding the classroom are out of the courtroom and into the halls and offices of the legislative and executive branches of government.” This sounded the court’s retreat.

Because he wrote the book on the WV Constitution and is moderating this discussion, I would be remiss if I didn’t share Professor Bastress’s thoughts about Pauley’s impact:

- Greater investment in education

- State has assumed a much greater share of responsibility for funding public schools

- A meaningful schools facilities system and investment in construction and renovation

- A very high degree of inter-district equity as measured by education dollars per student.

Robert Bastress, The West Virginia State Constitution (Oxford Univ. Press 2016)

I think the evidence supports each of these assertions and yet I’m not sure this means that the public education system meets the demands of the state constitution as interpreted by Pauley.

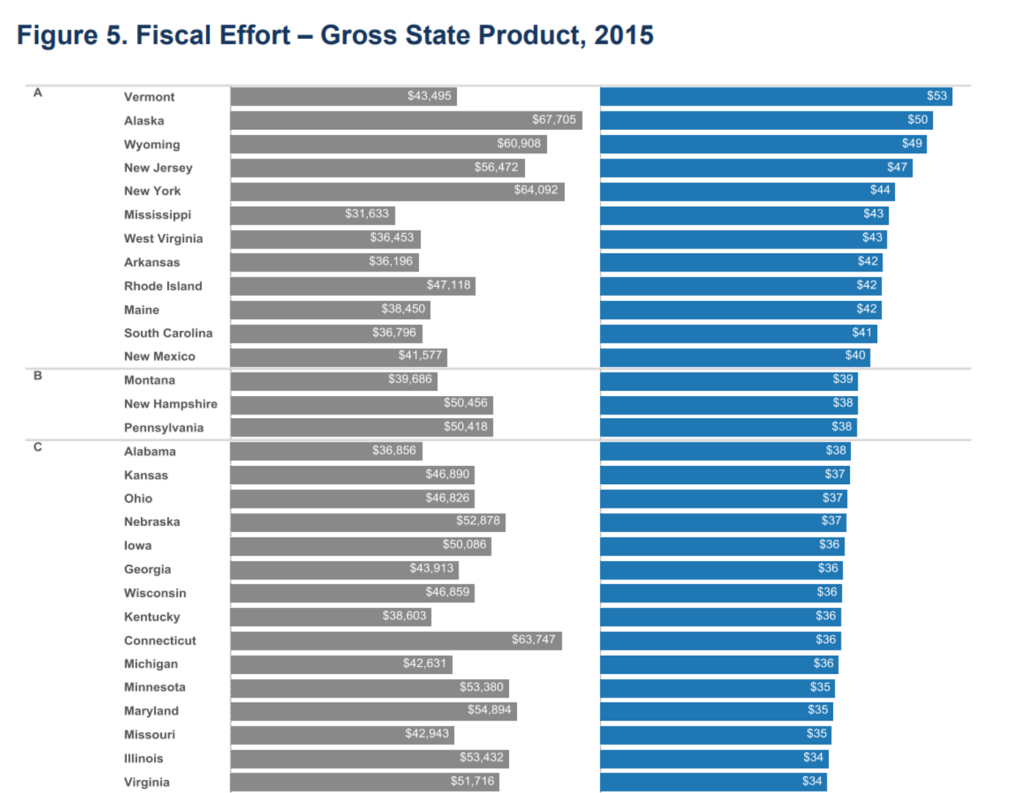

There is certainly greater investment in education. In fact, in comparing state education spending relative to the state’s fiscal capacity, in other words, state fiscal effort, WV ranks consistently high by that measure.

Is School Funding Fair? 7th Edition (2018)

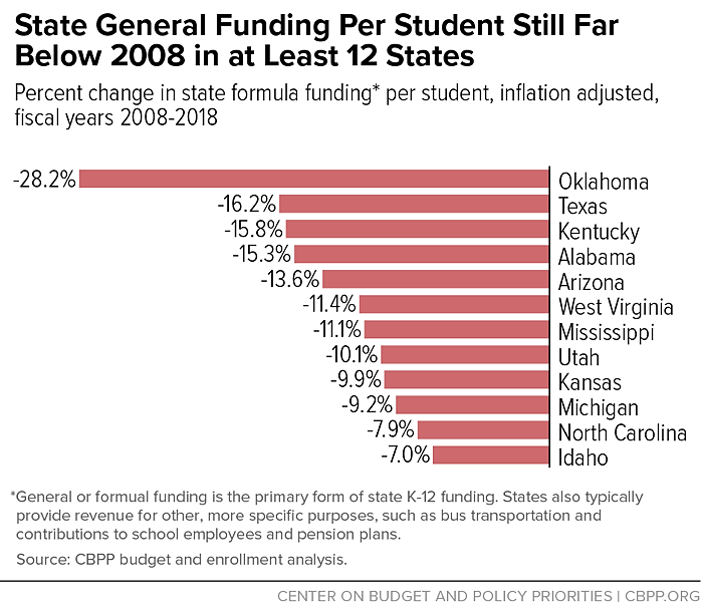

We fall in the middle of the pack in terms of spending per student. But we are spending nearly 12% less on education than we did before 2008, adjusted for inflation.

That doesn’t reflect Pauley’s declaration that the financing of education is the first constitutional priority.

Our funding formula is resource based meaning it determines the costs of delivering education in a district based on the costs of resources (mostly personnel cost). That’s in contrast to a student-based formula that assigns costs to the education of student, a base amount, and then accounts for the additional costs of educating specific categories of students that might be more expensive to educate.

While we are on the subject of personnel costs, I couldn’t help point out that WV has consistently ranked near the bottom in teacher salary and wage competitiveness.

Now a resource based formula may be fine if the goal is horizontal equity. And again Professor Bastress is correct, per pupil spending across districts is more equal. But remember that Pauley insists that’s not the ultimate goal.

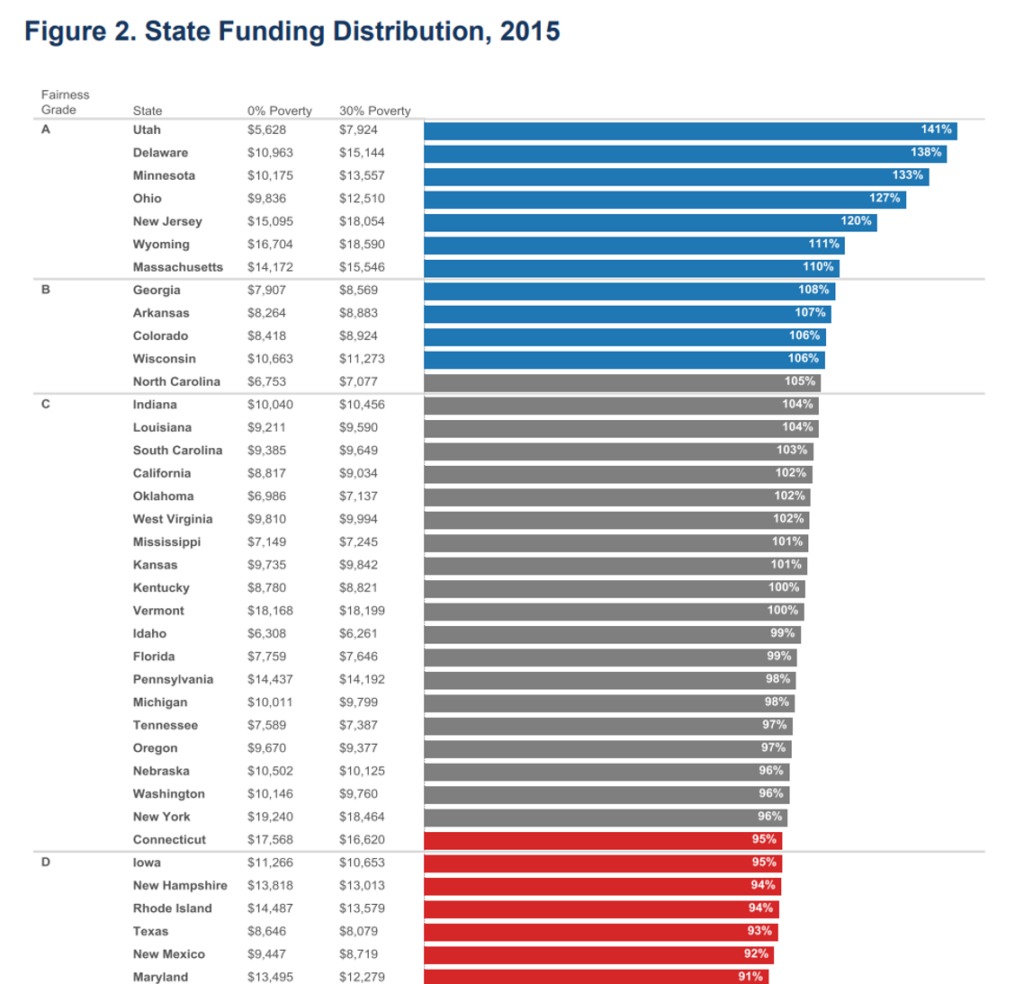

Vertical equity or spending adjusted to the needs of different students is what Pauley proscribes. And on that score, the state’s funding distribution has been regressive, the 2014 fairness grade was “D,” in 2015 we leveled out to a “C.”

Is School Funding Fair? 7th Edition (2018)

The trouble is we just do not direct enough additional funding to students from low-income households, even though the state’s program-based allocations consider poverty levels.

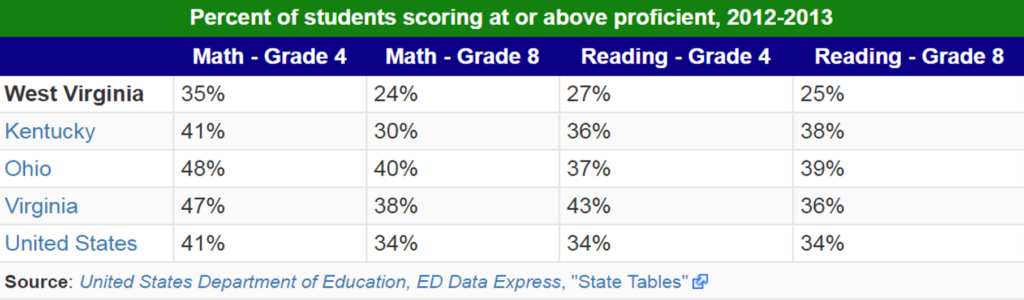

As for adequacy, the educational outcomes are not favorable, at least not those measured by test scores in math and reading, the two first capacities listed in Pauley.

By other metrics the quality of WV education ranks low; by this particular measure we rank 48th in K-12 achievement and chances for success. And we rank dead last as one of the least educated states in terms of the percent of population with post-secondary degrees.

Of course there are some favorable data points but I think the preponderance of the evidence suggests WV schools remain inadequate.

Now, unlike Justice Harshbarger, I haven’t lost hope. Indeed, I think there is hope for WV schools only because of the Pauley decision. But it’s going to take more than lawsuits and judicial action for real change to occur. And that may be the lasting lesson and legacy of Pauley.