No more than a day after it ended, the West Virginia teacher strike was heralded as “a possible catalyst for similar actions in Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Arizona; a harbinger of a new red-state populism to challenge the reactionary populism of Donald Trump; a resurrection of the glory days of labor politics; and, ultimately, a rare victory for public workers who have been buffeted by hostile, right-to-work statehouses and are bracing for a Supreme Court ruling that could gut union funding.” We can expect similar takes over the next few days, suggesting that the strike “could have lasting implications for the country’s schools.”

But even as I write this, the national media has largely moved on, diverted by another White House controversy. Social media clicks, shares, and scrolls will also soon subside. West Virginia teachers, parents, and students will be left once again to endure the inadequacies and inequities of the public school system on their own.

To the extent that a 5% raise and a PEIA task force help retain quality teachers or at least decelerate their exodus from the state, the teachers have done their part to vindicate their students’ constitutional right to education. No one could rightly fault them if they simply wanted to get back to their routine teaching challenges with a singular focus on finishing this year’s curriculum.

Any yet, if the overriding goal of the strike was to improve educational opportunity and achievement in this state, much work remains.

Consider that the 1990 teacher strike induced not only a $5,000 pay raise, a $42 million appropriation to PEIA, and a PEIA advisory board, but also an education summit followed by nine town hall meetings throughout the state, two governor-appointed education task forces, and a special legislative session devoted largely to public education.

The legislature passed the Education Reform Act and another bill to fund it. That Act, among other things, established a faculty senate in each school, created a center for professional development for teachers, required the adoption of new standards for teacher evaluation, promotion, and vacancies, put computers in kindergarten and first grade classrooms, encouraged training for county boards of education, and expanded bonding by $60 million.

It is perhaps unfair to compare the 1990 and 2018 teacher strikes given the current political climate. The public education system is also in a far better condition today than before the 1990 strike, so there was more to gain from the 1990 strike. And the 2018 strike might yet prove to be the flash point that compels lawmakers to reconsider the state’s investment in education.

But that will not happen by the sheer inertia of this moment; it will take advocates prodding that change along. West Virginia teachers have shown they are force to be reckoned with. “They have the leverage and courage of convictions that no others have.” And sure, teachers could exert that leverage at the polls in November. If all 20,000+ teachers vote in force, they will make up about 4% of the electorate, depending on turnout. But teachers know that they cannot put complete faith in politicians. After all, cuts in state aid have been made under both Democrat and Republican legislative majorities and governors.

Nor should teachers fully expect the other branch, the judiciary, to pick up the slack in enforcing education rights. The class action lawsuit that is reportedly being considered could take years to resolve. School finance cases in other states have sometimes spanned a decade or more. And even when the plaintiffs prevail in such cases, the remedy is almost never immediately forthcoming. The overwhelming majority of state courts defer to their legislatures to devise the remedy. Some legislatures have resisted at which point courts have few options.

“Courts cannot pass education budgets themselves and they cannot throw legislators in jail,” observes education law scholar Derek Black. “The most they can do is order the shutdown of schools (a dangerous game of chicken) or fine the state (which it may or may not actually pay).”

As I previously noted, “it’s going to take more than lawsuits and judicial action for real change to occur.” That is indeed the lesson of school finance litigation in West Virginia which began with a landmark supreme court decision in 1979 and ended in 2003 with the trial court terminating its long-running supervision of the case—despite remaining educational inadequacies—because the judge believed that the legislature and governor would do “what each says they are going to do.”

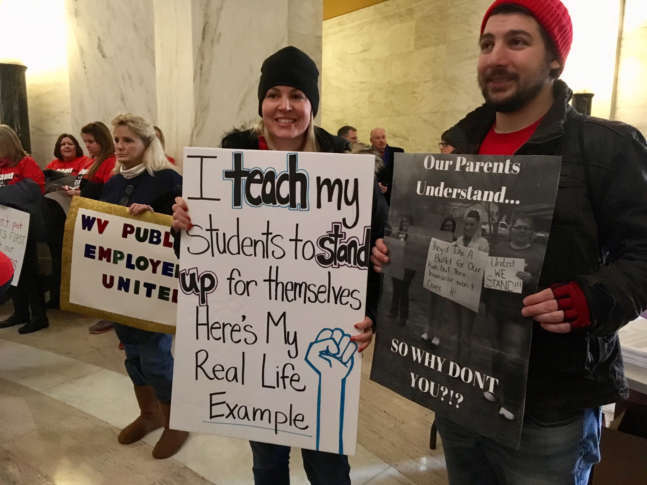

Well, those branches have not maintained fidelity with the state’s constitutional obligation to provide all children with an equitable and adequate education. And so, the burden may ultimately fall to teachers, parents, and, yes, even the students. Notably, it was a student walkout that lead to the first school finance case to make it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

We may not need a state-sponsored education summit, a task force report that few will bother to read, or even a costly, special legislative session. Teachers, parents, and students can convene their own statewide conference or task force, generate their own ideas for reform, and then descend again on Charleston, virtually or physically occupy the capitol en masse, until their representatives listen.

If that sounds naïve or farfetched, so did the 2018 teacher strike before it began. Teachers can seize this opportunity to lead, to set an example for the rest of the nation.

Because no one else is coming to the rescue.

Above all, teachers, parents, and students need to remain vigilant. Otherwise, the legislature, anticipating a lawsuit or a grassroots movement, could amend the constitution to weaken children’s education rights by limiting judicial review. A proposed amendment in the 2017 legislative session would have accomplished as much. Similar constitutional amendments to strip the courts of jurisdiction or dilute the right to education itself have been proposed in other states.