“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

―

Let’s make this easy for the Kanawha County Board of Education: Keeping the name Stonewall Jackson Middle School would not just be callously indifferent to its students, it would be legally problematic.

The “ultimate end” of the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education line of precedent is a “unitary, nonracial system of public education.” School boards that have intentionally discriminated by operating dual systems of schooling (one for whites, another for blacks) have an “affirmative duty” to eliminate the vestiges of past discrimination “root and branch.” The Equal Educational Opportunities Act codifies that duty.

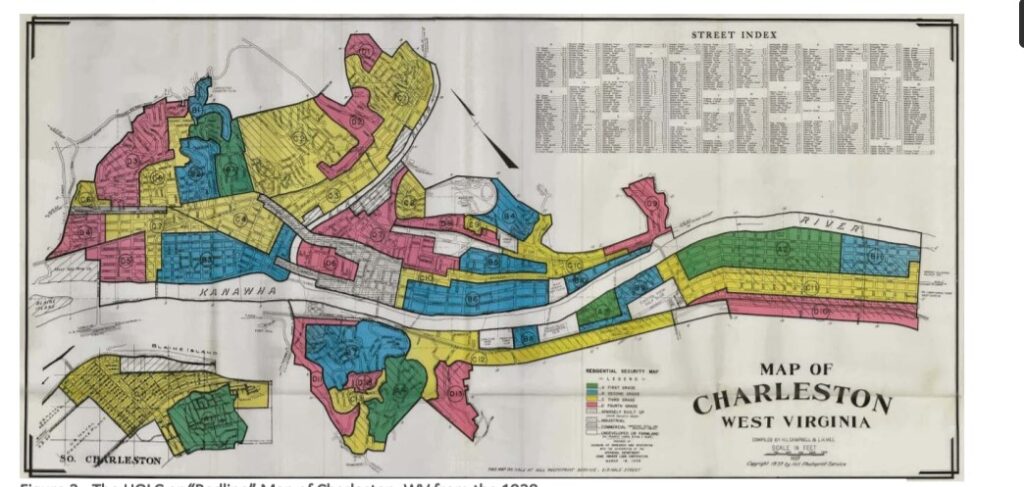

The Stonewall Jackson moniker affixed to the West Side middle school is a vestige of past racial discrimination with deep roots in the Charleston community. In the immediate years before the school was founded—first as a high school in 1940—“redlining and other discriminatory practices” stonewalled the black residents in the West Side neighborhood, impoverishing it “for decades.” The West Side has never recovered, it has one of the highest concentrations of African Americans in West Virginia, with roughly half of its residents living below the poverty line.

The school was named at a time when Confederate monuments were being sponsored nationwide by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Their influence likely played a role in the naming of the school. Regardless, the significance of naming the school in honor of a slave-owning Confederate general in this particular Charleston neighborhood was not lost on anyone. The history of the West Side, which “began with plantations, slaves”—5 plantations and 70 slaves, to be exact—was no dark secret. West Side streets bear the names of former slave owners and plantation features.

If that weren’t bad enough, the history is further tarnished by resistance to school desegregation.

Following the 1954 Brown decision, Kanawha was among more than a dozen WV counties that attempted to delay desegregation. It was not until the 1956-57 school year that the school board even approved a full integration plan. Yet as late as 1964, ten years after Brown, 40% of black students—and 7 out of 10 black students in WV counties with the most black residents—still attended all-black schools.

Those black students who were integrated from the all-black Garnett High School in Charleston were unwelcomed at the previously all-white Stonewall Jackson High School.

Today, half of the now-middle school’s students are minorities with “42% African American — the highest proportion among public middle schools in West Virginia.” To them, the history is no less relevant; indeed, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, it is all the more relevant and raw.

To be sure, there has been no determination that the Kanawha school board has engaged in discrimination of the like prohibited by Brown. And so it is not currently under any court-ordered duty to eliminate the vestiges of its pre-Brown discrimination. But that hardly means keeping the Stonewall Jackson name avoids all legal pitfalls.

Refusing to rename the school, when so many of its minority students and parents find the name so deeply offensive and hateful, makes the issue of race impossible to ignore, if not a motivating factor, and one that is bound to have a disproportionately adverse effect on the school’s racial minorities. That makes a decision by the Kanawha school board to keep the name susceptible to an equal protection challenge.

As a law student noted last year in the Virginia Law Review, equal protection claims have served as a basis for federal courts curtailing Confederate symbols in public schools before. “The retention of Confederate flags in a unitary school system,” one court observed, “is no way to eliminate racial discrimination root and branch from the system.” That court ordered the Confederate flag removed from the school because it was “an affront” to its black students—a decision the Fifth Circuit affirmed on appeal.

In another Fifth Circuit case, the court concluded that the school’s continued use of Confederate nickname “the Rebels” and the Confederate flag “would adversely affect the operation of a unitary system . . . by providing a continuing, visual focal point for racial tensions.”

And that is what the Kanawha school board risks by keeping the Stonewall name—escalating tensions that might provoke a racially hostile educational environment. If those risks do materialize and the school board is deemed to have been deliberately indifferent, it could be liable under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which could jeopardize federal funding.

As the Tenth Circuit has recognized, “when administrators who have a duty to provide a nondiscriminatory educational environment for their charges are made aware of egregious forms of intentional discrimination and make the intentional choice to sit by and do nothing, they can be held liable.” So, doing nothing here by keeping the name, will not necessarily insulate the school board from liability.

That said, equal protection and Title VI violations are difficult to establish. Explaining the limitations of federal law in attempts to remove Confederate symbols in public schools, another law student writes in the William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal, “Even a small object at sunset casts a long shadow.”

But federal law need not be the sole basis for such a legal challenge. The right to education is a fundamental right under the West Virginia Constitution, meaning it warrants the highest degree of constitutional protection. Therefore, “any discriminatory classification” is unconstitutional unless it is “necessary to further a compelling state interest.” Kanawha Cty. Pub. Library Bd. v. Bd. of Educ. of Cty. of Kanawha, 745 S.E.2d 424, 440 (W. Va. 2013).

In contemplating potential legal actions, the irony is that under existing Fourth Circuit precedent, the Kanawha school board could lawfully ban students at Stonewall Jackson Middle School from wearing disruptive Confederate flag apparel that might aggravate racial tensions. Yet certain members of the school board seem hesitant to remove the Confederate general’s name and mural from the school itself.

That would be “rewriting history,” they say. Quite the opposite, it would be confronting an ugly and painful part of our history in order to write a better tomorrow. This reckoning would be an act of redemption in the life of this school and the West Side community, encouraging difficult conversations about racism, as Rev. Dr. Fryson has said, “out of our healing, rather than out of our hurt.”

Do the right thing, Kanawha County Board of Education. Make the decision most aligned with the fundamental precepts of equality (and basic decency) our laws are meant to inspire: Rename Stonewall Jackson Middle School.