West Virginia lawmakers recently changed the way schools select textbooks and other instructional resources. Under the new law (H.B. 3089), county school boards will take over the task of selecting textbooks. The state board will maintain some oversight. For instance, publishers must still certify with the state board that their materials (1) meet evaluation criteria established by the state, (2) cover no less than 80% of the required content and skills for a subject as approved by the state, and (3) meet the lowest price available in the country.

But county school boards will otherwise assume primary authority for adopting textbooks. After decades of using a statewide adoption method, the impetus for this change is not obvious from the text, legislative history, or media accounts. But the change aligns with Governor Justice’s expressed views on the importance of local control over education policymaking. It also follows a national trend of state governments devolving control to local school authorities. Since the recession, that trend has been encouraged by states ceding control with fewer dollars spent on textbooks and by the backlash to Common Core, among other reasons.

So what does this change mean?

For context, textbook selection controversy is part of West Virginia history. The violent protests that erupted during the Kanawha County Textbook Wars in the 1970s made national news and inspired protests elsewhere. Ever since, the issue of who decides the content of learning materials has been a particularly sensitive and polarizing topic in the Mountain State. It’s hard to say whether this new law will incite further controversy, but the move provokes some immediate questions.

Procedurally, important elements of the transition remain unclear. Who can participate on the local review committees that county school boards must use in the textbook selection process? How is the 80% state-mandated content measured, regulated, and updated? What will be the form and content of textbook reports county boards must send annually to the state board? How will those reports be evaluated? What enforcement authority will the state board retain over textbook adoptions?

Policy-wise, the trend towards shifting control to the local level finds its roots in tradition and ideology. It is said that county-level administrators and teachers are closer to the students they serve and are arguably better positioned to select textbooks that meet their needs. But should there be significant differences in what children should learn in, say, Kanawha County versus Lincoln County? For perspective, the 20% variation in textbook content permitted under the state standards would, time-wise, account for more than seven instructional weeks per year.

And who should be permitted to weigh in at the local level to justify differences in textbooks? Florida recently passed a law (Fla. Stat. Ann. § 1006.28) that gives any resident of a county the right to a challenge textbook selection in a public hearing before a neutral officer. Proponents say the law permits experts to participate at the local level and thereby spares parents who oppose a textbook the time and effort to mount a challenge themselves. But, as I explain in a pending law journal article, the law could have unintended consequences. It does not ensure that local expertise is equally distributed among the counties. And the law applies to all books in schools, including library books, which aren’t always paid for by state tax dollars. It thus could result in “banned books” lists that very county-by-county.

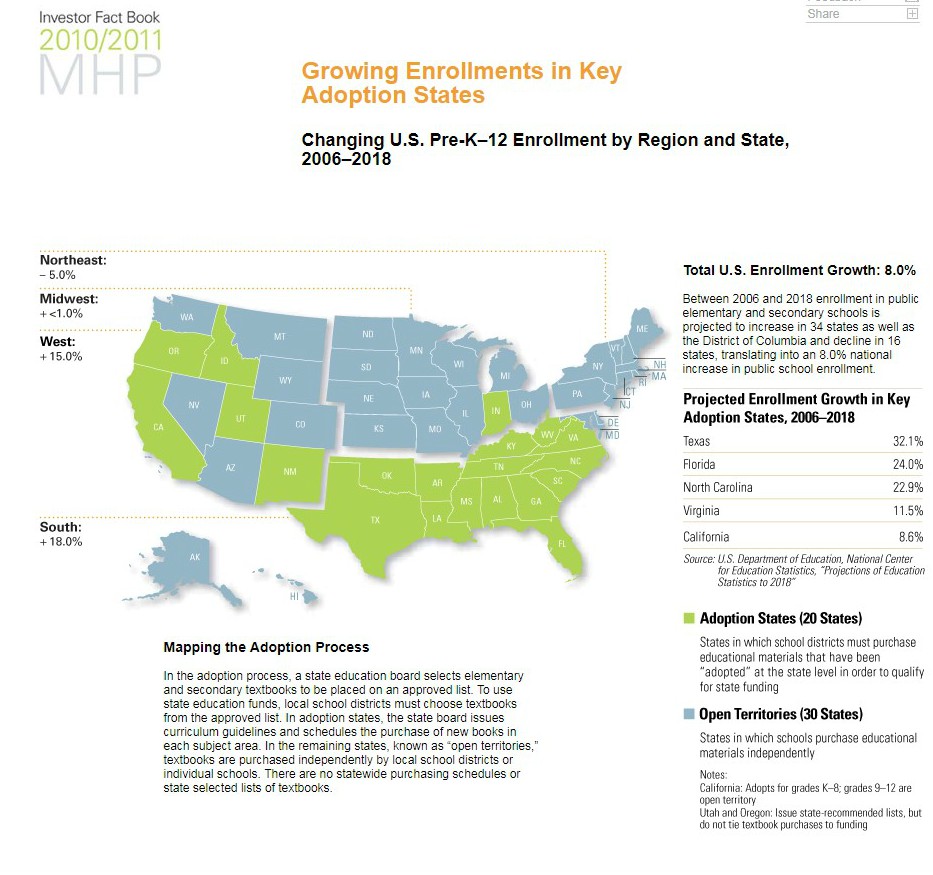

At the other extreme, decisions made at the state level ensure some degree of uniformity and consistency, which may prevent certain disparities. And yet, the reality is that 70% of textbooks are produced by only four major publishers and thus more populous states like California, Texas, and Florida wield considerable influence on textbook content, which few experts are satisfied with. Would increasing the number of decisionmakers down to the local level encourage more high-quality publishers to compete in the textbook market?

As with most things, balance is key in the textbook selection processes. West Virginia’s law incorporates some balance with its delegation to county school boards combined with continuity of some state oversight. Given the lack of clarity in the law’s intent and process, however, time will tell if indeed a proper balance has been struck.

Christine Pill has accepted positions at Bowles Rice LLP and with U.S. District Judge Irene M. Keeley following her graduation this May from the West Virginia University College of Law.