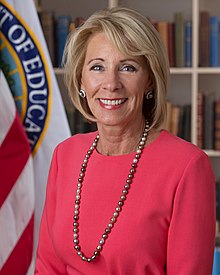

The U.S. Department of Education recently released proposed regulations regarding Title IX, the statute that governs how colleges and universities respond to sexual harassment and sexual assault on their campuses. The proposed regulations come a year after Education Secretary Betsy DeVos rescinded Obama-era Title IX guidance and include changes that have already garnered much attention, especially

(1) the proposal that would allow universities to choose to use a more stringent standard than “preponderance of the evidence” in campus hearings,

(2) the narrowing of the definition of sexual assault and harassment,

(3) the exclusion of much off-campus conduct from the scope of Title IX, and

(4) due process protections for a student accused of misconduct under Title IX, “including a presumption of innocence throughout the grievance process; written notice of allegations and an equal opportunity to review all evidence collected; and the right to cross-examination, subject to ‘rape shield’ protections.”

The reaction to the proposed regulations has been sharply divided, and neither side has “spared the hyperbole.” As I note in a forthcoming Denver Law Review article (exploring the use of restorative justice in campus sexual assault proceedings), the Obama-era guidance was heralded by some as empowering to campus survivors of sexual assault and attacked by others (including progressives) as impermissible rulemaking that inadequately protected the accused, unfairly targeted students of color, and chilled free speech on campus. The reaction to Secretary DeVos’s rescission of it was similarly mixed, dividing “thoughtful, progressive men and women of good will.”

Even assuming the proposed regulations come out of the notice and comment period looking relatively the same as they do now, the impact they have will be somewhat smaller in West Virginia than in other states, at least with respect to certain of the “new” due process requirements. The reason? We’ve had expansive due process protections for college students facing discipline for several decades now.

In 1975, Charles North, a fourth-year medical student, was expelled from the WVU School of Medicine for allegedly lying on his med school application. He challenged that expulsion as a violation of his constitutional right to due process. In North v. West Virginia Board of Regents, the West Virginia Supreme Court established certain due process protections that must be afforded to a student facing lengthy suspensions or expulsions, including

(1) a formal written notice of charges;

(2) sufficient opportunity to prepare to rebut the charges;

(3) opportunity to have retained counsel at any hearings on the charges, to confront his accusers, and to present evidence on his own behalf;

(4) an unbiased hearing tribunal; and

(5) an adequate record of the proceedings.

Thus, several of the due process requirements in the new proposed ED regulations—including confrontation rights and the right to an attorney—have been the law in West Virginia for more than 40 years. The inclusion of confrontation rights in the proposed regulations has been very controversial (one article deemed it the most controversial of the changes). Yet, at least in West Virginia, there has been very little caselaw interpreting North’s due process requirements, much less challenges to them, and it appears that the state’s two major universities have been following the guidance without further judicial instruction.

West Virginia University, for example, allows students to have an attorney participate in a student conduct hearing on their behalf, including in the questioning of witnesses, a rather unique policy that is likely due to the North decision. Further, the WVU Student Conduct Code permits the accused student to question “witnesses.” Marshall University similarly allows students to be represented by attorneys, although it restricts direct questioning of witnesses by requiring the accused student or their attorney to ask the question through the hearing officer.

As the proposed ED regulations move through notice and comment, they may change in response to feedback. Regardless of where the final regulations land with respect to confrontation rights and the right to be represented by an attorney at hearings, colleges and universities in West Virginia will continue to be governed by the North decision for the foreseeable future.

Amy Beth Cyphert is a Lecturer in Law at the West Virginia University College of Law and also the Director of the WVU ASPIRE Office, which assists students who are applying for nationally competitive scholarships and fellowships. She has served as a member of the WVU Student Conduct Board, but the information presented in this blog is all publicly available and was not otherwise obtained from confidential hearings or trainings.